Jean Edouard Côté grew up in the West End east of 149th Street, and was born in the old Misericordia Hospital. He’s a third generation Edmontonian, his grandfather, Jean Léon Côté, having come from the Charlevoix area northeast of Quebec City to work as a surveyor and civil engineer in the Yukon during the Klondike Rush. Côté’s parents, Jean Gustave and Cecilia (Taylor) Côté, who were married in 1938, built their house in the West End between 1939 and 1940, and Jean Edouard describes the process in detail in the attached transcript. His father worked for Canadian National Railway and his mother was a teacher-librarian.

In the interview, Jean E. Côté recounts his own school days in Edmonton’s West End, before taking a B.A. from McGill in Montreal, then a LLB (Law) degree from the University of Alberta, followed by graduate study in Law at Oxford. After articling in Edmonton, he joined a local law firm where he practised for 20 years. In 1987, he was was appointed a judge of the Court of Appeal of Alberta and the Northwest Territories, and in 1999, to the Court of Appeal of Nunavut. He retired in 2015, and continues to live in the West End and to write.

Jean Côté describes the walks he took with his father in the area, including west of 149th Street, and his observations about the neighbourhoods, their infrastructure, and the architecture. In the first video clip above, he describes watching how culverts were defrosted, the progressive building of houses by the owners in the 1940s and ‘50s, and seeing what he thought might be stables.

In the second video clip above, Côté recalls how MacKinnon Ravine and 149th Street were transformed in the late 1940s and into the 1950s. And in the aerial photo below from 1957, it is clear that the Ravine continued across 149th Street as he mentions. He explains how the west side of 149th Street was filled in to build the Loblaw’s store in 1958, and mentions some repercussions from that decision.

In the video, Côté also talks about a small sharpening shop built on stilts right in MacKinnon Ravine and the building which housed the first place of business in West Jasper Place for Barrel Taxi at 14901 Stony Plain Road. Elsewhere during the interview, he mentions other businesses and buildings that he noticed or remembered in the area: the Starlite Drive-In, the Meadowlark Shopping Centre and a gas station at the corner of 149th and Stony Plain Road.

He comments on reasons why people chose to live or to run a business in Jasper Place in those years:

It cost a lot less money to live in [the Municipal District or the Town of] Jasper Place than it did in the City of Edmonton …. The houses tended to be more modest, the shops were more modest.

The Town of Jasper Place tried very hard to succeed through shopping because, for years and years, the City of Edmonton not only absolutely forbade evening shopping – and of course federal law forbade Sunday shopping – and the City of Edmonton carried on that British practice of mandatory closing all shops on Wednesday afternoon, which was a nuisance. Every time you remembered, “Oh, my watch is broken,” or something, “I’ve got to do it,” – oh no, you’d let Monday and Tuesday go by – “it’s Wednesday, everything’s closed.” So, Jasper Place emphasized that, and as you’ve seen, the old pictures of the billboard – I don’t remember the billboard, I’m going by the photographs you’d given me – but those old billboards at the entrance of Jasper Place, two versions of it, always stressed shopping. Certainly, if you lived nearby in the City of Edmonton, you’d take advantage of that to buy groceries or something in the evening. But even into the 1950s when a lot of people had an automobile and were mobile and so on, people still had the habit of going downtown to shop. I don’t think Jasper Place ever fully achieved the shopping potential that its lack of closing bylaws and lack of zoning bylaws would’ve offered. The lumbermill and the lumberyard there might’ve attracted some business, but otherwise no.

When you look now at the old photographs of the businesses along Stony Plain Road – of which there are many iterations over many years – the buildings themselves are always very small modest buildings, some of which are quite old too. They’d been historic for years and yet nobody [had] put much money in them at all. It was a working-class neighbourhood.

In the early ‘70s, Côté and his wife, Pat, a librarian, purchased their first house in the Rio Terrace neighbourhood. By then, it was a part of the City of Edmonton, but had been developed in the early 1960s as a subdivision by the Town of Jasper Place. In the third video clip above, Côté describes that neighbourhood and its natural features, mentioning the former Jewish Community Centre at the bottom of 156th Street, which had been the Hillcrest Country Club.

From the transcript and the attached article written by Côté’s father for Alberta History1, we learn about his grandfather, Jean Léon Côté’s, work as a surveyor in the Yukon during the Alaska Boundary Dispute and as a Dominion Land Surveyor in Edmonton. Jean Léon Côté subsequently became a politician in the Province of Alberta, and then briefly in Ottawa as a Senator. As a provincial Cabinet Minister in the 1920s, he established the Alberta Scientific and Industrial Research Council – which is [now] the Alberta Research Council – where scientists first learned how to separate oil from sand. Côté, the grandson, also recounts a trip his grandparents and father made to Northern Alberta in the early 1920s in an automobile belonging to the E.D. & B.C. Railway which ran on the tracks during which they ran over a cow on the tracks.

In the 1910s, there was also a railway line that ran through the West End, including through what was then North Jasper Place, and Côté explains its history:

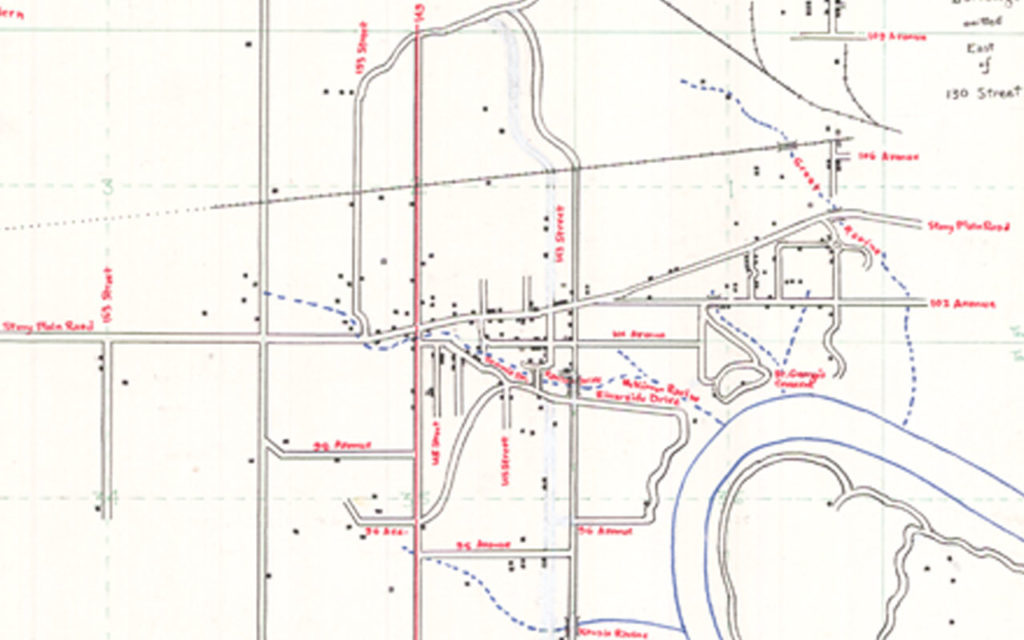

The Canadian Northern Railway wanted to build a line to Vancouver, [whereas] the Grand Trunk was going to build to Prince Rupert. The Canadian Pacific was already in Vancouver, but there was no route from Central and Northern Alberta to Vancouver, and nobody [else] proposed one. So the Canadian Northern was going to. On their first [attempt], they built [from Edmonton to the] Town of Stony Plain. Then, for competitive reasons [caused by] the Grand Trunk, they didn’t take [that line] any further. But that line ran roughly east-west, and it ran from the old EY&P line just a bit west of 124th Street to [the Town or Village of] Stony Plain through the western part of Edmonton. It was almost east west but was sloping a bit toward the south as it went further, so [it lay] about 106th Avenue. That ran right through, and that’s why that part of the Town of Jasper Place was called Canora. It wasn’t much of a [rail] line because it only went to the Town of Stony Plain. [….] [Later, after the Canadian Northern and the Grand Trunk amalgamated], the Canadian National naturally said, “Why do we have this stub line running to Stony Plain when we’ve got a better Grand Trunk line through Stony Plain?” So they tore up the [old Stony Plain] line west of 143rd or 144th Street. But I’m sure you’ve noticed that the survey of so-called North Jasper Place, which is really the [later] Town of Jasper Place, shows that rail line running right through it. [….] And [that rail line to Stony Plain was] earlier than the subdivision plan, so that’s why the subdivision plans show it. You ask yourself whether the person who drew up the subdivision plan for west of 149th Street allowed for the railway, because the railway is properly shown on his plan, it’s no part of the land he’s got to subdivide. I think in the case of west of 149th Street, I think some attention was paid to the railway line; not a lot, but some.

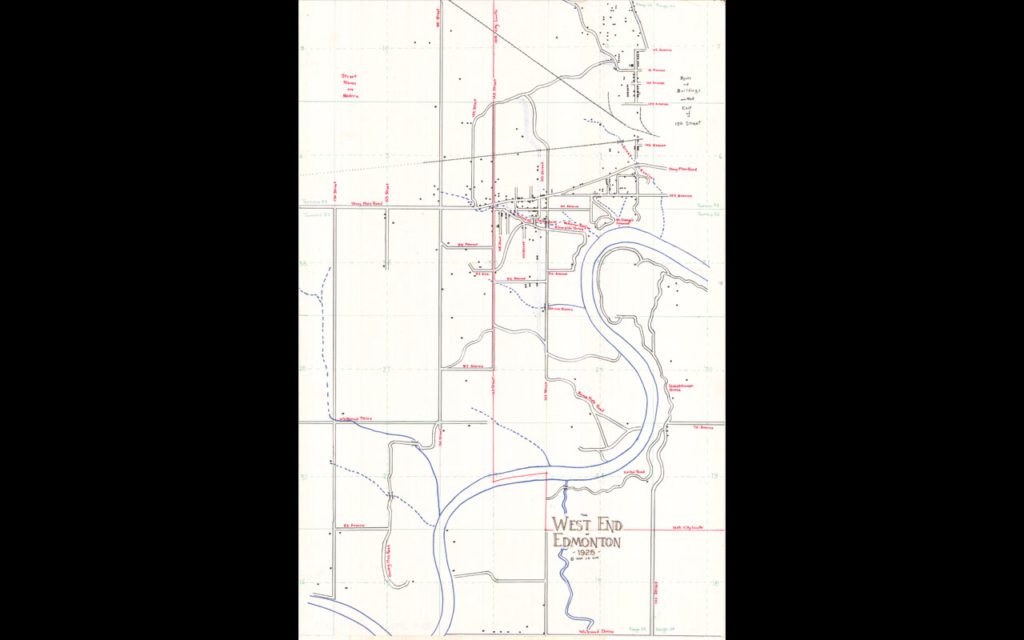

In the map below of the West End in 1925 made by Côté in the 1980s, he provides details of each of the houses and buildings that were present in the area at that time, and includes the natural features of the area. In it, we can see that there weren’t many occupants west of 149th Street as each dot represents a house or building. The railway line is also visible, and the dotted line reflects the fact that it was abandoned in 1923.2

Although Jean Côté retired in 2015, he has continued writing for legal publications and has written an unpublished book on the author of the Sherlock Holmes series, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. More recently, though, he’s carried out extensive research leading to a book entitled How Edmonton’s West End Began: A Hidden History, published by Juriliber Ltd., an established Edmonton book publisher on 106th Street:

I concentrate on the area between 142nd Street and 149th Street, so the Westgrove and the two Jasper Place subdivisions. [….] I rarely [use] the term “Jasper Place,” because it’s so confusing. Jasper Place used to mean east of 149th Street, now to everybody it means west of 149th Street. [….] I think I’ve found the answer to quite a few historical mysteries there. I think that I have discovered why the area between 142nd and 149th Street succeeded – not dramatically, but succeeded pretty well – and the other subdivision efforts east of 142nd Street – better funded, better planned – all fell flat on their faces. I’m trying to explain what I saw every day as a child, which nobody now seems to realize. [It is] that the West End did not start [developing] at 124th Street and move steadily west; the West End started at 143rd Street and Ravine Drive, of all the obscure places. There are real mysteries there.

In this wide-ranging interview, Jean Côté also touches on a number of other areas: how the political system in Alberta worked in the early 1920s during the time his grandfather was an MLA; his visit to the Legislative building as a child; issues in surveying in Alberta and Alaska during the Gold Rush, as well as in Australia; the Dominion Land Survey; the careers that his father and four uncles followed; his father’s work in the Canadian National Railway Archives and his writings; School Districts from the 1910s to the 1950s; the significance of the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation; how the construction currently taking place on Stony Plain Road has made him cautious to walk in the area; and, finally, how he “[likes] the idea of helping people own their own home by building it gradually in stages and building things as they have the money to do so,” as did his father and others in his family.

1Jean Gustave Côté, “J.L. Côté, Surveyor,” Alberta History, Vol. 31, no.4 (Autumn), 1983, pp. 28-32. [Article available here in .pdf. Reproduced with permission].

2City of Edmonton and Donald Luxton and Associates, Inc., Jasper Place Historic Resources Inventory, February 2019, pp. 26-27.