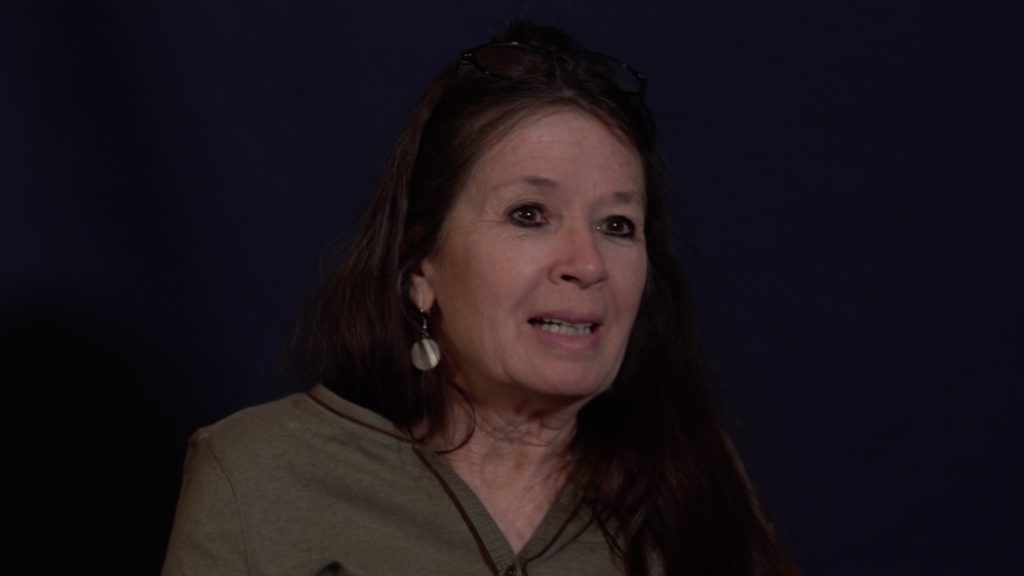

Joanne Lethbridge Pompana was born in the early ’50s and grew up on 149th Street and 91st Avenue across the road from the Town of Jasper Place. She remembers that there were gravel roads and farmland, and that Jasper Place felt like a “town-camp” with many Métis and First Nations people.

Joanne traces her paternal, Native family roots to the non-treatied Hunkpapa Lakota in Wood Mountain, Saskatchewan as well as to New Brunswick with Welsh and Seneca Iroquois heritage. Her paternal grandmother and step-grandfather settled in the Teepee Creek area of Northern Alberta, leaving Southern Saskatchewan a year before the dust bowl arrived there. On her mother’s side, her roots are from the Northern Scottish Isles, and her grandparents met during World War I. Her grandmother was an ambulance driver and her grandfather a wounded soldier. After the war, they came to Canada, and settled in the Grande Prairie area. Her parents had known each other in their school years in Northern Alberta, but reconnected when they happened to share a train ride back to Edmonton after World War II. They married shortly afterwards, and settled on 149th Street because it was close to both the country and the town. Her father pursued an Engineering degree in a Veteran’s program at the University of Alberta, and her mother worked at Eaton’s in downtown Edmonton.

At many points throughout the interview, Joanne describes the uniqueness of her Lakota Sioux culture and its teachings, philosophy and ceremonies. She notes that the Lakota (also spelled Lahcotah), or Teton, call each other Buffalo People (Pte Oyate / Hunkpapa or Tatanka Oyate). Her father’s family in Wood Mountain were associated with Sitting Bull, and performed as cowboys in his rodeo. She also mentions that her husband’s (Cliff Pompana) mother was a descendant of Sitting Bull and Black Elk, also from Wood Mountain. She recounts that Pompana was “singled out by Black Elk when he was nine years old to carry the culture”.

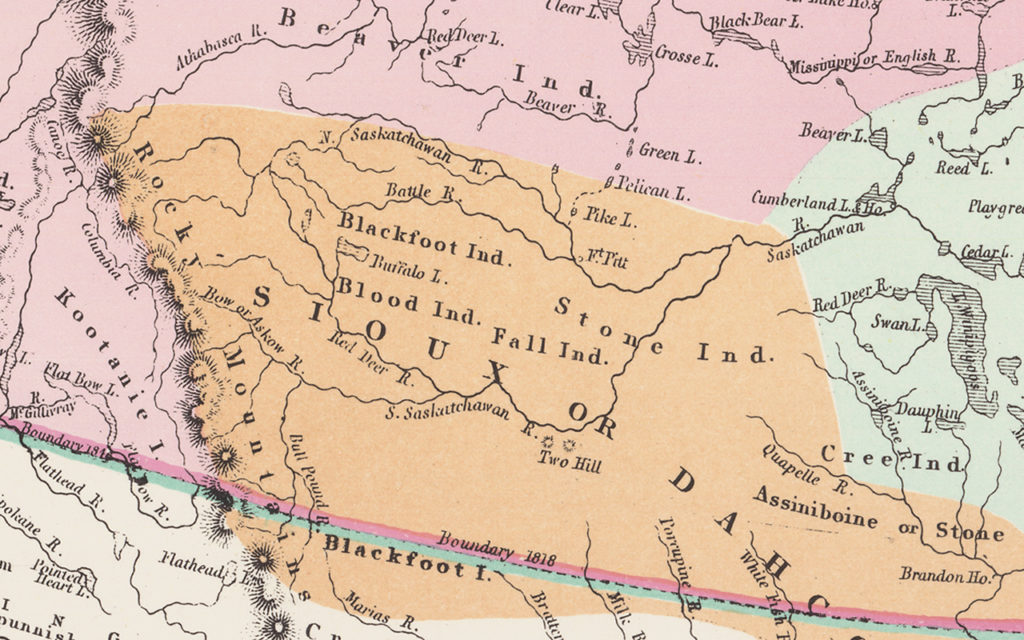

Through oral history, Joanne learned that her people roamed three provinces and ten states in the West, following seasonal food sources and the buffalo migrations, and so that they could trade and participate in large gatherings such as the Sun Dance ceremonies. When Joanne began to explore her heritage, she came across a map drawn by Hudson’s Bay Company employee, John Arrowsmith, which confirmed the presence of the Siouan and Stone peoples in Alberta. The discovery of that map and her work as an interpreter at Fort Edmonton made her aware that Edmonton had been a major trading junction for Indigenous peoples from far and wide.

She recounts how this migration has continued in contemporary times and drawn many more Indigenous peoples to Edmonton. For example, many Northern folk, including Inuit and Dene, were airlifted to Edmonton between the 1940s and the 1960s to be treated at the Charles Camsell Hospital because of the tuberculosis epidemic, and then for polio and other diseases. She recalls that many Indigenous people – families from Yellowknife, Fort Chipewyan, the Dakota Sioux Nation, Métis dancers – lived in Jasper Place when she was young. Many came to work, usually for very low wages, at industries such as the Lilydale Hatchery and on farms in the area.

A thread that weaves through the interview speaks to the fact that, from the 1960s to the 1980s, barriers existed that led people to hide their Indigenous roots. For example, her father hid his heritage while he was an engineer in the oil patch, only rediscovering those roots when he went to a Siouan centre in South Dakota. Joanne meanwhile indicates, “it took me a long, long time to get sorted.” Even in Jasper Place, she says, “[the Indigenous] presence was not talked about”. Today, however, she notes that Jasper Place has a large and varied population of Indigenous people reflected, for example, in the multiple origins of the Indigenous students studying at the Yellowhead Tribal College in The Orange Hub, and in the proximity of Enoch Cree Nation and Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation.

Joanne also talks about growing up on 149th Street in the 1950s and ‘60s, and how she appreciated its sense of community. She remembers going down to the zoo parking lot to attend the Muk-Luk Mardi Gras, a winter carnival, when some of the activities were held there in the mid-1960s, with its dog sled races, ice sculptures, straw bales and ice mazes. She fondly recalls how pleasurable it was to be outside in the community in those years, being able to walk everywhere on the grassy footpaths; dogsled- and bumper-riding with her brothers and neighbourhood playmates; mud fights across 149th Street; going to see Ben Hur at the Starlite Drive-In; and crossing 149th Street to shop at Tooke’s, the Chinese grocer’s. She also recalls having milk delivered by horse and cart.

Joanne Lethbridge Pompana is director of the RED ROAD, INDIGENOUS WEST, PTE OYATE, FAMILY RESOURCE NETWORK, which is housed in The Orange Hub. It was co-founded by Cliff Pompana and herself with a “unique approach based on Lakota teachings and relationship with the Earth.” She is also a mediator, counsellor and lawyer, and was the recipient of an Esquao Award in 2016, presented by the Institute for the Advancement of Aboriginal Women.